The Essence of the Shamanic Experience

Over countless thousands of years, shamanic myths and rituals of connection kept alive the awareness of the existence of an invisible spirit-world or soul-world whose symbol, initially, may have been the mysterious dark phase of the moon.

Out of that darkness the crescent was continually reborn—symbolically associated with the regeneration of the earth’s life and, in the traditions of Vedic India, with the regeneration of cosmic cycles, each lasting hundreds of thousands of years.

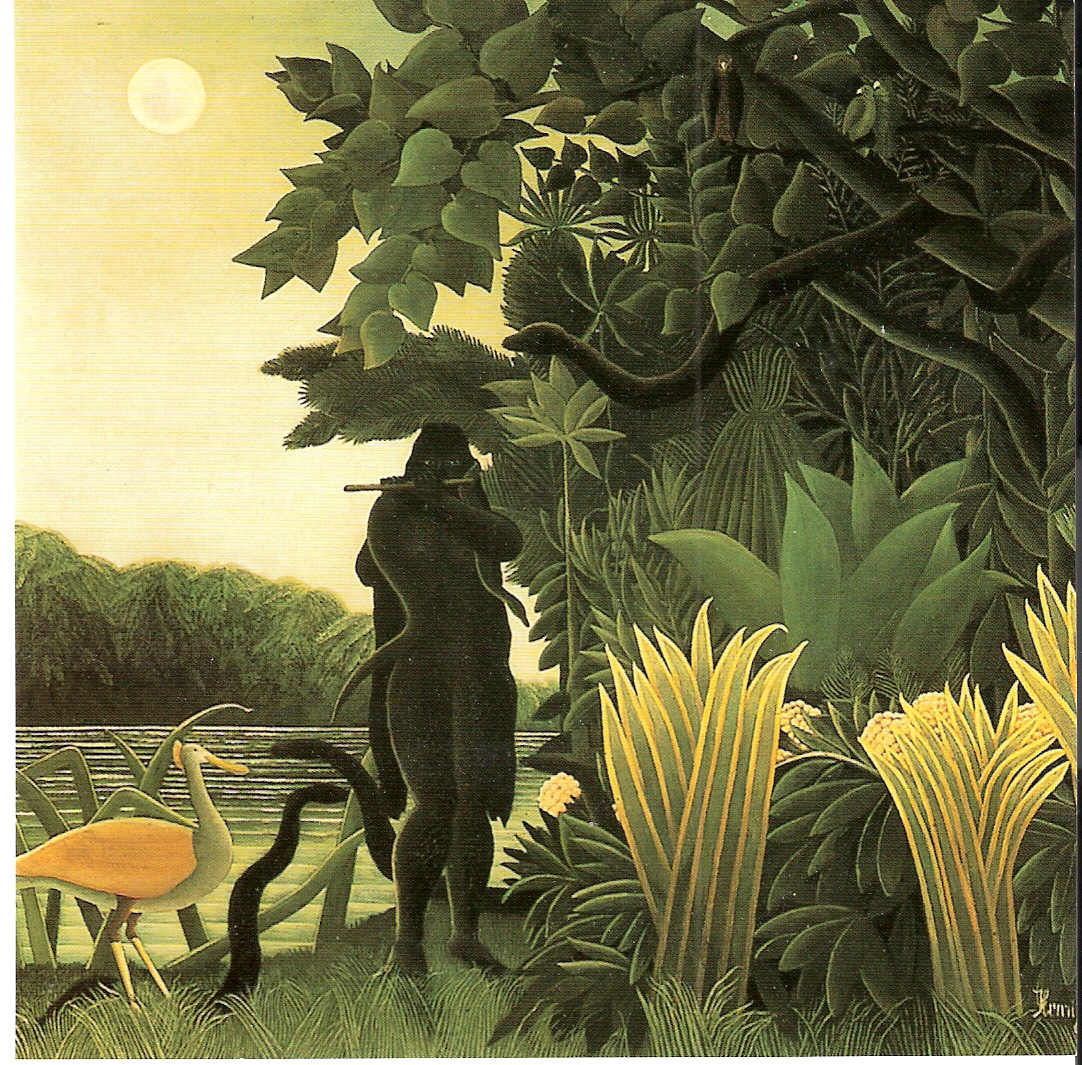

Poets, artists, seers and musicians received their inspiration and their calling from the starry cosmos that was as real to them as this world.

Shamanic cultures knew there was no death.

They were in touch with the ancestors.

They knew about travelling to other worlds.

Greece had the Eleusinian Mysteries that gave people trust in their survival. Long before Greece, Bronze Age Egypt had a very detailed description of the journey of the soul after death. This extraordinary civilization was as aware of the spirit-world as of this world. People lived in awareness of the presence of the spirit-world and the goddesses and gods who inhabited the starry cosmos and descended each day into their temples. Far from seeing death as extinction, the Egyptians saw death as a journey towards awakening to cosmic life.

Living within a Sacred Order

People did not so much believe in gods and goddesses as encounter them, as vividly described in the Iliad and the Odyssey. They may have heard these beings speak and received wisdom and guidance from them or seen them in their dreams. Because the clear distinction we now make between an inner and outer world did not then exist, and because they felt they lived within a Sacred Order, the psyche of that time lived within that Order, in communion with it.

The words spoken, the music heard, the dreams and visions seen came not from ‘inside’ them, but from the soul of the cosmos, from daemonic beings, goddesses and gods and the spirits of animals, trees, mountains and rivers as well as from the ancestors who were never thought of as dead but who formed a continuous line of connection with the living. Oracles could impart the will of these beings and people knew that they were not alone in this world but could be guided and influenced as well as threatened by unseen entities. Birds were recognized as messengers of this invisible world, very possibly because people dreamed about them in this role or even heard them as a voice speaking to them.

The earliest legends about the great oak tree at Dodona in northern Greece, said that oracles were delivered by the oak itself and that when birds happened to alight on the tree, the tree would suddenly begin speaking with a human voice. The Oracle at Delphi was the centre of the Greek world where the celebrated priestess of the Oracle, or Pythia, as she was called, received embassies from all over the Greek Empire. She held the title of “The Delphic Bee” and was the highest authority in that world, intermediary between the supplicant and the god Apollo.

A highly developed intuitive sensibility, acute powers of observation and the ability to listen to the spirits of plants, trees and animals, taught people to gather, grind or distil certain herbs and plants or the bark of trees for healing illness.

Dreams and visions were of great importance in the diagnosis and healing of disease. Methods of divination predicted the advisability of taking certain courses of action. From all over the Greek Empire, people travelled great distances to the many healing sanctuaries of the god Aesclepius — the most famous of which were at Epidaurus, Kos and Pergamum (now in modern Turkey) — to be healed of their diseases.

Here, as also in Egypt and Crete, the main diagnostic agent was the dream, sometimes a visionary dream of the god himself. As one man who was healed of his long-standing illness described it, in words that leap out vividly from a forgotten past, “One listened and heard things, sometimes in a dream, sometimes in waking life. One’s hair stood on end; one cried and felt happy; one’s heart swelled out but not with vainglory. What human being could put this experience into words? But anyone who has been through it will share my knowledge and recognize the state of my mind.” Rites of incubation, travelling in the spirit-world and healing were practised in caves and sacred places all over the ancient world.

Like the astronomer-priests of Egypt who communicated with the stars, or the Taoist sages of China and the Vedic seers of India, withdrawn into the deep solitude of the mountains and forests, the shaman-seers who guided these cultures were trained to enter a state of utter stillness, to listen and bring back to their community what they heard in an enhanced state of consciousness.

What we now call synchronicities were an intrinsic and recognized part of the experience of the people of that time because they had the intuitive ability to notice things far more acutely than we do today.

At the heightened level of awareness that characterized the participatory consciousness of these cultures, everything had the ability to communicate—a stone as much as a star, an animal as much as a tree or a spring gushing out of a crevice in the rock.

The unseen soul of nature had the potential to reveal itself in the flight of a bird, the stirring of the leaves of an oak tree, the ripples on a lake. Nature was held to be animate, conscious and able to communicate with man. The essential characteristic of lunar culture was kinship — the kinship of man with all creation — reflected in the much quoted words of Chief Seattle:

Every part of this Earth is sacred to my people… We are part of the Earth and it is part of us. The perfumed flowers are our sisters. The bear, the deer, the great eagle, these are our brothers… The shining water that moves in the dreams and rivers is not just water, but the blood of our ancestors… The water’s murmur is the voice of my father’s father. The rivers are our brothers. They quench our thirst. They carry our canoes and feed our children… Remember that the air is precious to us, that the air shares its spirit with all the life it supports. The wind that gave our grandfather his first breath also receives his last sigh. The wind also gives our children the spirit of life…Will you teach your children what we have taught our children? That the Earth is our Mother? That what befalls the Earth, befalls all the sons of the Earth. This we know: the Earth does not belong to man, man belongs to the Earth. All things are connected like the blood which unites us all. Man did not weave the web of life, he is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself.

I am the Brother of The Forest and Must Defend it

The recent words of David Kopenawa Yanomami, a contemporary Amazon shaman and tribal leader, speaking about the calamitous destruction of the Amazonian forest, reflect the same awareness of kinship: “I am the brother of the forest and must defend it.”

The Whispered Lineage of the Dalai Lamas

From another part of the world, the following story may perhaps illustrate how long- atrophied faculties once connected us with the soul of nature. Next to the Potala Palace in Lhasa there is a temple called the Lukhang or “Temple of the Serpent Spirits” that the present Dalai Lama describes as one of the hidden jewels of Tibetan civilization. This temple was the private chamber of the Dalai Lamas, the place where they retired for deep meditation. Miraculously it has not so far been destroyed by the Chinese invasion of Tibet. The walls of the upper floor are decorated with extraordinary paintings describing the Tantric practices of the Dzogchen path to the direct experience of reality—the path practised by the Dalai Lamas for centuries. Only these murals depict the practices that were otherwise transmitted orally, and poetically referred to as “the whispered lineage”.

Prior to the Chinese invasion of Tibet on one day each year, the Lukhang was open to pilgrims who crossed the lake to the temple to make offerings to and invoke the blessing of the water spirits believed to reside beneath the lake. This ritual went back to a time when the Potala Palace was being built and a deep pit had been excavated to provide mortar for the palace walls. Legend says that a female water spirit or Naga came to the Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682) during his meditations and warned him that the work on the Palace was destroying the Nagas’ ancestral home. The Dalai Lama promised that he would build and dedicate a temple to the spirits of the lake which had formed over the desecrated land so that their presence would be recognized and honoured.

A Different Kind of Consciousness

In our modern world, fairy tales like the “Sleeping Beauty” may be the residual fragments of the forgotten participatory experience where forests were inhabited by creatures who would help or hinder us; where spirits of tree and mountain, stream and sacred spring could speak to us and reveal the secrets of healing plants and waters; where bears or frogs might be spirits in disguise. Shamans or hermits, old women or men living in the deep forest or mountain hermitages might offer us wise counsel, or birds bring us messages, warning of danger and acting as guides. There are countless fairy tales, descending from ancient oral traditions, which describe how the hero or heroine who responds to the mysterious guidance of animals or who helps them when others have ignored their requests wins the reward of the treasure and the royal marriage. They are the creation of a different kind of consciousness, one where the mythopoetic imagination was highly cultivated, honoured and developed and where story-tellers who were often seers held a place of honour in the community.

People in the Polynesian islands still sing to the sharks to come to the boats of the fishermen, asking their permission to kill them for food. The Maori shamans of New Zealand still believe that everything has its own life force: the stone has the life force of the earth itself, the bone the life force of all living things, the shell the life force of the sea. In carving these elements of life with the patterns they observe in nature, they carry this insight into their work, believing that it brings healing power to the wearer and to the community. The ‘life’ of the stone, bone or shell is never lost. Its energy lives on in the wearer of the carving and is transmitted to the observer.

Out of this profound relationship with the landscape in different parts of the world, myths developed, specific to the people who inhabited it for millennia. As Frederick Turner so brilliantly expressed it in his book Beyond Geography; The Western Spirit Against the Wilderness,

Living myth must include and speak of the interlocking cycles of animate and vegetable life, of water, sun, and even the stones, which have their own stories. It must embrace without distinction the phenomenal and the numinous.

This is something that has been forgotten and that is why we have no living myth today.